Solarpunk is broken. It's going to take some weird lateral moves to fix it, and one strange Steampunk strategy might offer a solution.

I have a problem with -punk. Not punk, punk's doing ok, punk's got Against Me! so it can't be doing too bad. No it's -punk, the wide range of abnaturalist aesthetics that've sprung up after Cyberpunk, that I have an issue with. Your Steampunks and your Solarpunks and your Biopunks and probably Seapunks (though was that ever a movement or was it just a few oddballs producing late 90s style CGI?), those movements just rub me the wrong way.

Take Solarpunk. Solarpunk blends Art Noveau aesthetics with a sustainability message, envisioning a future where extractivist corporations are replaced with clean energy and the wonders of Sustainable Science. A tumblr post describing Solarpunk as "the most important science fiction movement of the last 20 years" opens by describing one of the movement's key qualities:

- It’s hopeful. Solarpunk doesn’t require an apocalypse. It’s a world in which humans haven’t destroyed ourselves and our environment, where we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet. We’ve learned to use science wisely, for the betterment of ourselves and our planet. We’re no longer overlords. We’re caretakers. We’re gardeners.

And another key post lists off a litany of aesthetic, technological, and social concerns, "Tailors and dressmakers!" and "Communal greenhouses" alongside "Natural Colors!" and "Art Nouveau!" And, of course, there is an economic plan: "Less corporate capitalism, and more small businesses!" the post suggests breathlessly.

There's no denying Solarpunk is a movement built on hope. That's most of what Solarpunk has going for it. It has, after all, no major works of literature or art, and its ostensible members have not instantiated its values in any large scale way I'm aware of. I've seen a number of posts of people garlanding their hair with a mix of vines and LED lights, and TV Tropes has excitedly catalogued all works of science fiction that include "solar sails" and declared them Solarpunk, but there's just not a lot to Solarpunk beyond an aesthetic and a nebulous political project for Saving The Earth. One of the lists of "notable events in the development of Solarpunk" cites, as an event, the deletion of the Solarpunk wikipedia page. It also seems to include but two anthologies of short stories in a decade long history.

To an extent I could end the critique here and be good, and for that matter I could extrapolate to many other -punks and still be basically correct. Cyberpunk was undeniably a cultural force with an astonishing number of significant works--Snow Crash, Ghost in the Shell, The Matrix, and Neuromancer all standing out. Steampunk has The Difference Engine, I suppose, and (wicki wicki) Wild Wild West but outside of Neil Cicierega remixes it's hard for me to think of a persistent cultural presence for Steampunk on par with Cyberpunk's persistence. Simply observe the way the Internet responded to the news that Hobby Lobby's owners have been smuggling thousands of Mesopotamian clay tablets by immediately making a flood of jokes about Snow Crash's convoluted plot involving a billionaire using Sumerian code to hack the human mind.

That's not to say that there aren't attempts to create a solid Steampunk canon, of course. Cherie Priest's Clockwork Century series is one such attempt. Priest's explicit ambition to create a genre-defining series was boosted when she secured a Hugo nomination for the first book, Boneshaker, and for me, at least, there's much to admire in her approach. For one thing, Priest is aware of the dopey reputation of Steampunk. In a 2013 press release for her fifth and final novel in the series, for example, she pictures a skeptical reader proclaiming, "[the book] is probably just gears on hats and curly mustaches for no reason!" The books, at least the first two books, do deliver on the promise of stories that are more than just a fashion choice, whether gears on hats or LED lights in vines.

Priest is right to pitch her stories as being more than just the usual waxed mustache aesthetic. There is, at least in the first two books, real depth to Priest's world, a punk sensibility that centers the relatively powerless as heroes, and tech that never goes too far beyond the possibilities of the age but still seems at turns monstrous and wondrous. I want to talk about all these aspects of the books because I think they're all critical to reintroducing a kind of spirit of -punk to a nascent movement like Solarpunk. Today, though, I want to focus specifically on maybe the best most brilliant way Priest improves the Steampunk formula:

She adds in zombies.

No, fuck you I'm serious, adding zombies to Steampunk is genius. I mean obviously she's not JUST adding zombies, this isn't Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, but the zombies really do carry a lot of symbolic and thematic weight in the story. Moreover, the lateral move adding zombies represents parallels moves made in Cyberpunk--the association between hacking and ancient sorcery in Neal Stephenson's work notably--and parallel moves that we might make in Solarpunk as well. What parallel move would that be? All in good time! Let's break down what zombies do for the Clockwork Century series first.

These novels take place during an even more protracted, bloody, and miserable Civil War. Railroads cross the country, used by both sides to move mammoth trains and, occasionally, stranger engines of destruction from front to front. Far south, the Republic of Texas finances itself by selling technology to the Confederacy and eyes Emperor Maximillian's Mexican empire warily. To the west are neutral, largely ungoverned territories. And in the north-west, where the first book, Boneshaker, is set, lies the walled city of Seattle, or what's left of it.

The wall that rings the city isn't to keep people out.

It's to keep the zombies and the heavy, toxic gas that created them in.

See, before the series proper begins, a massive mining engine, the titular Boneshaker, went out of control on a test run. The way it leveled the main square of Seattle was bad enough. But on top of that it also ripped into some underground chamber full of a gas that rapidly began enveloping the city and turning the inhabitants into shambling, ravenous corpses.

Yeah, it's fucking awesome.

I could talk about how the narrative--about a middle aged woman going into the city in the hopes of finding her missing teenaged son--is way more punk or -punk than any damn story about aristocrats with clockwork on their corsets, but that's better left for another article. What really interests me here is the introduction of this foreign, strange element into the Steampunk genre upends the genre's problems.

Part of this comes from simple horror. The addition of horror to Steampunk feels necessary to me to an extent, if only because the nightmares of the Victorian era have been so utterly sublimated by Steampunk-as-fashion. The Civil War, of course, was a horror show, arguably the first massive modern war, caused by an even greater horror show: American chattel slavery. The wealth of Europe and America was built on such crimes against humanity, colonization and extermination carried out all over the globe. The Victorian era was characterized by horrific working conditions for ordinary people, stifling social norms, the pathologization of sexuality, and on and on and on. This is the world that Steampunk resurrects.

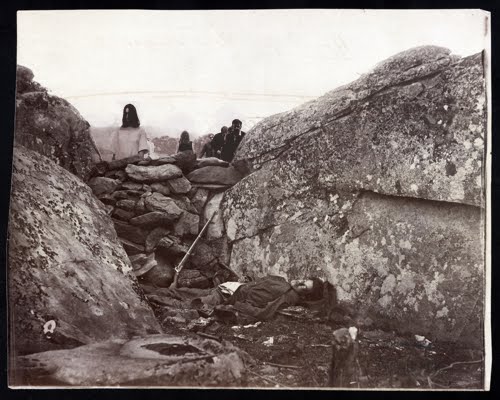

I increasingly feel like a big meanie when I point such things out. Increasingly in fandom spaces there seems to be consensus that raising such problems intrudes on the harmless escapist fun that the fashion represents. And yet... I can't shake the feeling that we have, narratively, some responsibility to account for this history, some responsibility to the dead. The editing of the past was already begun in the past itself--Timothy O'Sullivan's civil war photograph above was edited even before I added a crowd of Night of the Living Dead zombies into the background, the actual body in the photo dragged by Sullivan from elsewhere so that he could get the shot he wanted. If we're going to be fucking around with the past anyway, it seems worthwhile to fuck it up in a direction opposite the impulses to sanitize and aestheticize.

Certainly it seems hard to argue that Solarpunk should be above such concerns. It is after all an avowedly political movement, a movement designed to effect real change in the world! So... why the reluctance on the part of Solarpunks to recognize the full magnitude of the problem, the sheer horrible scope of the problem of catastrophic climate change? How can we take seriously future world that has avoided the apocalypse when the apocalypse is right at our door? As I write this I think of the city-sized iceberg that just today split off from the Antarctic. I think too of the recent New York Magazine article entitled, grimly, "The Uninhabitable Earth." The article is based on a simple observation: we have culturally decided that the middle case scenarios of global warming are the worst case scenarios, ignoring very real ACTUAL worst case scenarios:

The present tense of climate change — the destruction we’ve already baked into our future — is horrifying enough. Most people talk as if Miami and Bangladesh still have a chance of surviving; most of the scientists I spoke with assume we’ll lose them within the century, even if we stop burning fossil fuel in the next decade. Two degrees of warming used to be considered the threshold of catastrophe: tens of millions of climate refugees unleashed upon an unprepared world. Now two degrees is our goal, per the Paris climate accords, and experts give us only slim odds of hitting it. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issues serial reports, often called the “gold standard” of climate research; the most recent one projects us to hit four degrees of warming by the beginning of the next century, should we stay the present course. But that’s just a median projection.

Let us assume, he said, that we are fucked.

Solarpunk, in the projected context of resurgent fossil plagues, mass refugee status for the entire equatorial region, sunken cities, famine, and, perhaps, extinction, seems woefully unprepared, delusional. In this it mirrors Cyberpunk that strayed from the Gibsonian model (the grim model where most of the world is relegated to slums while corporations rule over their fiefdoms--you know, the model that actually came true) and Steampunk that sought only to elevate and glorify an imagined Disneyland Victoriana.

In this context, the addition of zombies to Steampunk has additional weight. Zombies are symbolic. This shouldn't come as a surprise to anyone who's seen a George Romero film. They are a mechanism to make things visible--prejudice, or mindless consumerism, or authoritarianism. In the Clockwork Century books they make visible the Steampunk dead. They make visible the cost of technological advance through their genesis, a powerful engine gone horribly out of control. Through a drug--sap--harvested from the toxic Seattle smog they turn people oppressed by poverty, desperation, and trauma into corpses that can still walk around for all to see (though at one point a Union officer remarks that sapheads do not survive combat for long, and are useless for anything but cannon fodder).

Their status as symbols becomes most tangible in the second book, Dreadnought. The story circles slowly around a mystery that at first seems only tangential, the mystery of a whole battalion of Mexican soldiers and Texan civilians who mysteriously vanished somewhere north of the Rio Grande. I'm going to spoil the mystery: they got zombified. Over the course of the story the characters, thrown together coincidentally on the train the Dreadnought, piece together that an airship carrying the toxic Seattle gas crashed in Texas, turning battalion and civilians alike into a shambling hoard.

That's just the conceit of the story's climax. What's really interesting is what Priest does with this conceit. First, she adds to the train a caboose guarded by a strange doctor who, it turns out, plans to synthesize from dead sapheads a chemical weapon that can be used to mass-zombify confederate troops. Then, she puts the Dreadnought into combat with the Shenandoah--a combat that first seems to end in the Dreadnought's defeat, and then develops into horror when the Shenandoah is overwhelmed by the zombie hoard and the Dreadnought's soldiers must decide whether to come to their enemies' aid. (They do. Only three soldiers survive anyway.) Oh, and of course the disappearance of the soldiers in the first place heightens tensions between Texas and the Mexican Empire, threatening to tip the two countries into open conflict once more.

In this context it's impossible to deny what the zombie hoard represents: they are the cost of the war--both its direct horror consuming Union and Confederate soldier alike, and the long term horrors unleashed by the wartime technology boom. Is a mass zombification chemical weapon so different, after all, from the chemical horrors unleashed in World War I? World War II? Vietnam? By allowing the dead to get up and walk again, Priest allows them to both exact a dark revenge on the living, and to make tangible the way the conflict has spiraled massively out of control in a way that threatens to engulf people that are, for the most part, simply trying to survive.

The dead of Steampunk, then, speak simply by shambling around and refusing to lie down. In this sense, they are hauntological. Part of the impetus for theorist Jacques Derrida's invention of "Hauntology"--it's ontology (a theory of being) but with ghosts, because puns--is his desire to theorize a way of speaking to the dead. This is important if we're seeking after Justice, Derrida suggests.

I think.

Look, this is literally the most dense theory I've ever read, so to an extent here I'm stumbling through Derrida's oblique suggestions and trying to make sense of it. I'm planning on doing a whole Let's Read Theory on Derrida's hauntology book Specters of Marx but it's taking forever because I honestly am having such a difficult time parsing out what he's saying.

Nevertheless, what I'm getting from Derrida is the idea that the dead can't speak, so we need some way of bridging the gap between the dead and the living (and the past, present, and future) in order to account for them in our system of justice. The Ghost for Derrida is a kind of spooky intermediary that can be present and not-present at the same time. In Mieville's adaptation or appropriation of Hauntology, the ghostly is the repressed coming back to the surface, Industrial Capitalism's shadow bleeding out into the material world.

Priest's zombies are tangible but they are, nevertheless, undeniably, horribly, dead, the dead, walking dead who can't speak but who might speak to the nightmare that underlies Steampunk's clockwork dream, simply by refusing to lay down and stay dead. For the Clockwork Century books, they represent a threat, but they also may represent an idea of justice that counts the cost of the steam age. The climax of Dreadnought, when soldiers from one side attempt to rescue those from the other from the zombie hoard, suggests a jarring loose of the mechanisms of war (and of war profiteering--the chemical weapons specialist who plans to create Zombie Gas seems primarily interested in achieving acclaim and fortune for himself). It may even suggest that the rank and file of both sides, workers, freed slaves, enlisted men, have more in common with each other than the technocrats running the war. The engines both literal and figurative of the Clockwork Century are runaway engines of destruction, and my sense of where the narrative is going suggests that the machine must be prevented from working at all.

It's probably not that you need zombies in order to write about these topics, of course. Otherwise historians would have a real rough time of it. Nevertheless, it seems notable to me that some of the best sort-of-Steampunk is also New Weird fiction: Fallen London and the Bas Lag novels certainly have a lot of steam powered stuff running around, but they're far more interested in the aesthetics of the Weird than steam power per se, and they are certainly deeply shot through with critiques making use of the weird or the hauntological to make tangible the violent horror of their industrial capitalist settings. It's not even that weird for -punk to go in this direction. After all, as noted earlier, Stephenson has his occultism just as Mieville has his tentacles, and maybe occultism is a good way of making visible the way code operates demoniacally, unexpectedly, with a mind of its own. It's not exactly hard to draw parallels between Peter Thiel and Elizabeth Bathory, of course, and if the demon that gave him his power was a digital one, well... the story might end in a similar place regardless.

I mean, you could dispense with the search for a strange lateral move entirely, and focus on answering global climate catastrophe with something a little more revolutionary than "small capitalism uwu." I don't deny that. But at a certain point if we're talking about speculative fiction we may as well speculate wildly and weirdly, and the introduction of the incongruous can sometimes do, through literalizing the figurative, what political consciousness alone can't. So, for the sake of this article, let's keep following the surrealist impulse. But... zombies don't really feel of a piece with Solarpunk, even if the thought of the slavering hoards battering against the reinforced glass of someone's sustainable greenhouse is appealing. And sorcery is almost too obvious, a power fantasy in which we magic away the trapped arctic methane and bubonic plague. No, Solarpunk already has far too much magical thinking. What could represent a kind of lateral move for Solarpunk?

To me, cryptids fill the obvious slot here--thematically associated while still somewhat estranged from Solarpunk's weird ideology that wishes Aesthetic Spiritualism to exist unproblematically alongside Heroic Scientism. Cryptids are a pretty complex and disparate bunch of critters, of course--they can range from the merely unidentified and unclassified (the Okapi, identified by European scientists in 1901, or the King Cheetah, a color variant identified only recently), to survivors of prehistoric extinction (like the improbable but real coelacanth), to folklore creatures that may have some basis in fact (Mieville, again, immortalizes a 40 foot giant squid specimen as the "Kraken" in his book of the same name).

The appeal of cryptids seems pretty obvious. Sure, they exist only nervously with the breathy scientism of Solarpunk, but I'm ok with that for the most part because, for an ecological movement, they represent the possibility of entities that evade us, haunt us, exist in a state of uncertainty and ungraspability. Surely, if Solarpunk is interested in being not a dominating force over the earth but just one force among many natural forces, cryptids hover right at the boundary of the known and unknown, acting as a reminder that we're part of a system that we do not have unassailable mastery over. The existence of periodic Montauk Monsters is a reminder, too, of runaway processes within our industrial society that might give rise to strange monsters. Maybe that's the domain of Biopunk, but Biopunk isn't exactly any more of a thing than Solarpunk is, so it doesn't seem unreasonable to splice elements of one into the other (particularly given the entities involved).

What really interests me however is one particular subset of cryptid. Today I saw a video that might or might not be of a Tasmanian Tiger, thought extinct since the 1930s. I'm not going to lie, it was a weirdly emotional experience. I've been obsessed with cryptids since I was a kid--my first real Special Interest (before I discovered Magic the Gathering) was Fortean shit, and at various points I suspected strongly that the UFO I saw one night had actually abducted me. (I should've checked the clocks! Always check the clocks!) But Tasmanian Tigers are sort of in a different category from other weird monsters, because unlike dinosaurs lurking in the Amazon the Tasmanian Tigers were here tantalizingly recently, and then... they weren't.

And it was all our fault.

Tasmanian Tigers exist in the center of the venn diagram of forteanism and environmentalism, and having an interest in both meant that things like dodos, passenger pigeons, and the tigers had a kind of privileged position alongside those tragic soon-to-be-cryptids like the beleaguered tapirs losing their habitats or manatees getting caught in boat propellers. The discovery of colossal squid under the arctic was cool, but it was just cool. The discovery that the tigers survived human butchery would be something else entirely. It would be, in a word, redemptive--proof that maybe we haven't fucked things up so colossally that they cannot, in small ways at least, be fixed.

This is what I want from Solarpunk, I think--or one thing I want from Solarpunk, at least. Solarpunk as it stands feels a lot like "green technology"--a series of tweaks that make for good branding and style but don't rock the boat too much. Where is Solarpunk's militant side? Where is the rage and pain? Where is the accusatory question: "Who killed the world?"

The loss of a species is a planetary trauma, even if it is one that we might repress on the individual or pop cultural level. If we are part of complex assemblages, however, where all kinds of nonhuman actors from purportedly dead matter to companions species to larger net systems and interactions that all have agency and ability to take action, the crippling of pieces of those assemblages, and our replacement of their organs with profit-driven cyborg parts (replacing British Columbia and Alberta's carbon-clearing forests with a system to pump cooling-but-toxic gas into the air for example)... well, surely we can't expect that our place within the assemblage will remain unchanged?

And Solarpunk's solution seems to be... farmer's markets.

If the loss of a species is a planetary trauma, the resurrection of the Tasmanian Tiger would represent a more concrete hope, a hope that this trauma might be overcome without resorting to toxic coping mechanisms. It would represent the possibility of renewal. Solarpunk posits "a world in which humans haven’t destroyed ourselves and our environment, where we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet." What the Tasmanian Tiger reveals, however, is that this is not our world. We have not pulled back just in time, we cannot turn and awaken the dead and piece together what has been smashed. If the Tasmanian Tiger might return to us a ghost, a cryptid, then that would be hopeful, it might point a way toward a Solarpunk that is about Justice, Justice that speaks to the dead.

Steampunk needs its zombies to remind us that industrial capitalism desperately would like to bury its dead. The Victorians had their seances; they were pursued by spooks. Part of being a steam punk is to side with those spooks and haunt the parts of society that can put their dead to rest or try and summon them like servants.

Solarpunk needs its cryptids to remind us that we are haunted by a hoard of the nohuman dead, a black hoard that, like the passenger pigeon, might blanket and blacken the sky for miles and miles. Solarpunk needs to contend with these beast ghosts because they are a marker of the real damage done to the world. Solarpunk should hope to contend with these beast ghosts because they hold the possibility of a return and rehabilitation, an easing of trauma, an imperfect but real closure of the wounds in the world.

I couldn’t see a donation button anywhere on the blog and can’t subscribe to your Patreon, so I bought A Host of Gentle Terrors as a thank you, because this article is just terrific.

ReplyDelete"Where is the accusatory question: 'Who killed the world?'"

ReplyDeleteAh, for that question to apply, the world would have to be dead, yes? What I think might be even more appropriate for solarpunk would be for it to be too little, too late. For the world to already be doomed. Perhaps even without most inhabitants of the solarpunk world knowing they're doomed, since the purpose of doing all these little mitigating things even though doom is approaching would be to lengthen whatever moderately tolerable climate remains and keep people from a final despair with the worst kind of hope: impossible hope. A futile solarpunk fiction for a readership that is highly likely to inhabit a future where the only options left are futile, to mirror how Gibson's slums-and-corporate-overloards vision came to pass.

This is not to the exclusion of cryptids, of course.

For me the failure of Solarpunk is the inability to address a)disability and b)religions other than modern paganism. As a disabled Jew I found, in Solarpunk spaces, an inability to address the needs of either group.

ReplyDelete