What is it that makes today's Pop Team Epic's so different, so appealing? And can it explain why people hate the marketing for Ready Player One so damn much?

The theme song of the anime Pop Team Epic opens with a vintage TV set showing a number of partial clips of the protagonists Popuko and Pipimi. Here they are shown looking like normal anime characters... but this quickly gives way to the real aesthetic of the show and its source manga. The final shot of this sequence depicts the two characters in their squat, simply drawn cartoon forms, running towards the camera, flipping off the viewer with unsettling, more realistically rendered hands.

Then, right as the primary melody of the song begins and the title is displayed, a bat with nails hammered into it smashes the TV screen. The series begins, to the sound of peppy j-pop, with its own dramatic annihilation. The camera lingers over the title and the shot of the obliterated TV screen for several seconds. That's a pretty good introduction to Pop Team Epic and its whole format--a bewilderingly fast series of several second clips that are seldom associated with anything around them, and pretty broken in terms of their internal coherency. Pop Team Epic comes pre-shattered for your viewing pleasure. That's a bit part of its specific brand of pop art.

After a series of animated comic panels from the four panel gag strip series that is Pop Team Epic's source, we get into the main first visual sequence of the opening, in which Popuko and Pipimi are displayed in a wide series of contexts. What's primarily interesting in these shots is the implication, repeated all over through the show's various sketches, that Popuko and Pipimi are some sort of mass produced consumer good. Pipimi's hair oozes out of a nozzle onto her head. Popuko is squeezed out of a toothpaste tube, and peers from an unzipped pencil case. Pipimi's face is uncovered via a vacuum cleaner run along a floor. Popuko faces are extruded as tubes like clay or plastic canes and sliced off by automated machinery into thin Popuko discs. Pipimi is dolloped like some sort of batter onto a waiting assembly line. Popuko churns back and forth inside a washing machine.

Popuko and Pipimi are treated here not as characters which we as viewers understand to be human, but as mass market goods and household items. Later in the opening they don a variety of costumes, as though to suggest that they might take on any role (not that unusual for sketch comedy) and then don a variety of forms, as though to suggest they might take on any position within daily life itself. Milk cartons, one tall and one short. A champagne glass and a wine glass. A broom and a dustpan. A banana and a strawberry. A ruler and a protractor. Pipimi and Popuko can, it seems, be interchanged with just about anything (if they keep the same basic size relation and share some notional connection) while maintaining, in some sense, their Pop Team Epicness. They may be consumer goods but they are in some sense every consumer good, with the stipulation of their particular interrelationship, like some kind of cute anime currency, a commodity exchangeable for anything else. Popuko and Pipimi are very nearly shitpost gold.

This sense of mass production and repetition is baked into the show. Wanting to create a fast 15 minute program, but lacking a second show to play after Pop Team Epic in the half hour time slot, the creators opted to take the same episode and simply play it twice with minor alterations. The largest variation is always that one version is performed by two female voice actors, and the other is performed by two male voice actors. This, paired with the fact that the VAs for Popuko and Pimimi change every single episode, unvoices the characters--makes it impossible to ascribe one voice to them as their true, canon representation. Once again they seem to be indefinitely modifiable and replaceable, the show and characters always existing in multiple forms.

This mirrors the fandom engagement with the show, as far as I can tell. I mean, Pop Team Epic isn't unique in the way its episodes and the original comics are converted rapidly into memes and ways for making commentaries on other stuff. That's a huge part of how humans seem to engage art. Pop Team Epic just anticipates that dynamic and builds it into the deep tissue of the show. This tacitly acknowledges and endorses this fannish behavior. In this way, Pop Team Epic's aesthetics carry real weight.

Its aesthetics, in short, draw heavily upon pop art traditions, from the early practitioners like Andy Warhol in the 50s and 60s, to contemporary artists like street artist Banksy and superflat artist Takashi Murakami. What these artists hold broadly in common is an interest in appropriating the aesthetics of mass produced goods, mass media, and pop culture, jumbling those aesthetics together, smashing their media apart, or repeating them in various mechanical or iterative ways in order to create new aesthetics.

Pop Team Epic is, in a sense, pop art returning home to mass tv broadcasting and internet streaming. It's up front about what it is and what it's doing. Now the trick is figuring out just what we think of its particular brand of pop art.

~ poptepepic ~

Pop Art has its ups and downs.

The movement sprouted up from the hypercapitalist white picket fence world of tomorrow it's-just-got-to-be-the-dawn-of-the-morning-of-time bullshit of the middle of last century, and at its best it took a satirical scalpel to consumer culture. Advertisements, cheap comics, magazines... the infinitely reproduceable images and texts of the day were so much raw material for these artists, and the results were often comical parodies of The Good Life, or experiments in making that Good Life weirdly alienating. At its best, pop art then and now is a kind of revolt, a way of taking the information constantly blaring at us from all sides and asserting some sort of active role in the proceedings.

At its worst pop art simply stripmines pop culture for raw material that it can repackage for the wealthiest assholes on the planet as ironic pastiche of what The Poors are into. The worst is, in other words, Roy Lichtenstein, famous for tracing other people's comics. Remember when the son of Gene Simmons of Kiss was revealed to have copied or straight up traced a bunch of stuff from famous manga Bleach? That sure was weird. Anyway, it was pretty dumb of Nick Simmons to sell his comic to scrubs instead of to billionaires, because when you do the exact same shit--vis, redrawing other people's comics worse--for billionaires, you instantly go from being a failson to being a famous artistic genius.

This summary isn't a prescription but a presentation of two extreme takes on the same phenomenon (and also an opportunity for me to slag off Lichtenstein). In fact I'm kind of leery of even explaining what I'm doing in this article at all because I'm super not into the idea of any of this turning into some checkbox metric for distinguishing Good Pop Art from Bad Pop Art. And if I present a list like so:

[]Whose interests does this pop art serve?

[]What context makes it possible?

[]What is its attitude toward the pop culture that it draws upon?

[]Who is making it?

[]For what audience?

it's really easy to treat it as a series of binary checks that aggregate to some Pop Team Index.

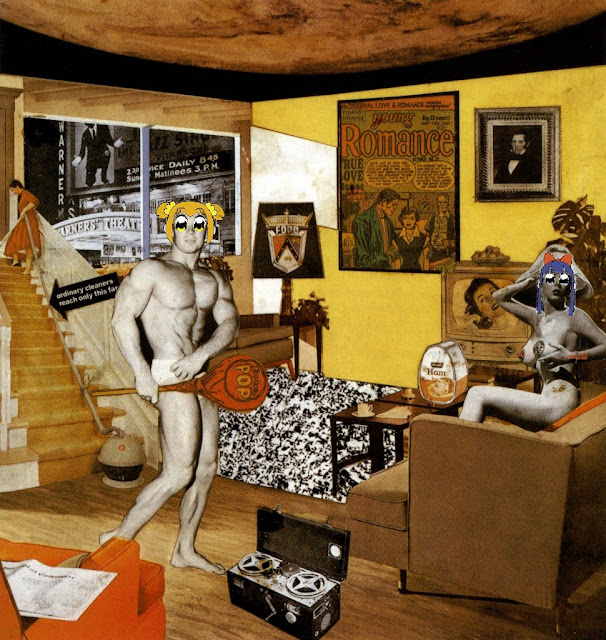

That's not really what I'm going for there, though. Rather these are the kinds of questions that I find circling around in my brain as I'm looking at pop art, and they often intersect in complicated ways. Like, a lot of early pop artists have the same general attitude towards the stuff they're working from. There's a sense in this art--like the original version of "What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?" which heads off this article--of pop culture, marketing, comics, TV, theater, fashion, food, the hired help, sex, gender, and so on as all being part of the same flat horizon of freely usable materials. The artist, Richard Hamilton, creates a parody of the Modern Home by taking mass culture and shoving it all into the same space, overwhelming the viewer with references until the whole thing overflows into absurdity. The highlight of the piece has got to be the Charles Atlas muscle man posing with a giant lollipop, helpfully labeled "POP", held over his dick. I mean it's not subtle, but it is funny, and that counts for a lot I think.

At one point in a recent episode of Pop Team Epic two of the voice actors break character to have a conversation about the show. Noting that a character shares key features, a strikingly similar name, and even a voice actor with a character from the popular series Detective Conan, the actors question whether Pop Team Epic can get away with the blatant lift, and describe the show creators as "fearless". That counts for a lot too, that sense that a pop artist is really getting away with something, doing something outrageous, maybe being a little bit shocking. It's not just that it's treating pop as part of the horizon of usable materials, but that it's happy to pilfer and plunder if it needs to. Pop Team Epic isn't being produced by people who have the clout needed to license Mickey Mouse, or even Dastardly and Muttley, so when those characters appear in the show they appear as pixelated areas, just a few colors and voice cues suggesting what the show is appropriating. This is the compromise needed to make that flat pop horizon possible.

That riskiness doesn't stop the show from grabbing whatever it can get its grubby paws on and playing with it the way a kid plays with action figures. In one sequence Robocop shows up momentarily to lose an arm wrestling match with Popuko. In the second version of that clip, one of the voice actors hails Robocop as "Daft Punk!" This kind of nonsense, where famous figures show up in the background for no reason, are misidentified or behave radically out of character, and disappear while the main skit occurs around them, is pretty common in the show. They're just there to be posed, handed their metaphorical giant lollipop to hold in front of their dicks, and are ushered off screen again by the impatient judges Popuko and Pipimi.

This kind of thing, this free use and abuse of characters in a massive multiplayer crossover context, is really only possible in a few places. It's possible in marginal spaces where kids or other folks who still like to play, in some sense, with action figures can hang out without worrying about The Man shutting them down. It's possible if you can get someone to fund your pop art, and they have lawyers who can tell you how exactly to get away with playing your various games.

And, of course, it's possible if one or two media companies own 90% of our culture and can freely use any of the images and ideas they claim without fear of reprisal, or of any competition.

~ poptepepic ~

Ready Player One is coming for us, whether we want it to or not. Based on some book, and directed by Spielberg for some reason, the story is about all your favorite whatsits from the 80s, plus Tracer from the not-even-slightly-overhyped "moba" (cockney for "mobber") game Overwatch, all existing together in some virtual world that holds the fate of the Earth in the balance, for some reason. Have you ever wanted every god damn character from an 80s movie plus Tracer to punch each other at the same time in high def 60 frames per second? Well now, apparently, you can! Because like three corporations own so damn much of our culture now that nothing on heaven or earth can stop them from making Blade Runner's titular protagonist Blade the Vampire Hunter kill Bart Samson in a hit and run accident while driving the famous time traveling DeL'oreal from Back to the Future if some executive decides that's a good idea. And if we can't stop it, we might as well enjoy it right?

We will enjoy it. We will be so nostalgic we die, and when we do we'll vomit out pixel art coins so the executives of the world's copyright holders can swim around in them like Scrooge McDuck. Remember Ducktales? YOU BETTER REMEMBER DUCKTALES YOU LITTLE SHIT I'LL CUT YOU. Buy some merch!

From what I gather, there's an extent to which Ready Player One is a story about a quest to find non-pathological ways of engaging pop. The evil corporate goons trying to defeat the hero (the 'Sixers, who finally got tired of losing basketball games I guess and decided to try for world domination instead) are out to fully control the simulated world of OASIS and turn it into a micropayment filled hellscape. Rebelling against that makes perfect sense. Spaces in which fandom operate may be, as Daniel James Joseph points out, places where fans perform tons of free labor that ultimately benefits corporations... but there's a sense in which that work is understood by fans as liberated and dynamic, and the imposition of more overt capitalist exchanges, as (to use Joseph's example) Bethesda attempted to do with their paid mods program, is as a result often met with striking resistance to this attempt to colonize free time and free exchange of labor among fans. Turning recreation into simply another arena where we are always working or, perhaps, can do nothing but simply consume what's put before us does seem pretty nightmarish.

But this model of passionate but utterly hollow fandom where to be a fan is just to consume is, flatly, exactly what the advertising for Ready Player One promotes! This is a film marketed entirely upon product placement. Remember when we used to complain about product placement? Now Tracer showing up in her skin tight body suit in a blatant marketing deal with Blizzard is actually somehow a selling point, or at least the people producing the ads believe it will be!

Pop Team Epic is no stranger to the warped side of fandom, and in fact derives tons of humor from obsessive subcultures. Popuko's constant freakouts in response to people consuming media in casual ways are funny precisely because they're so excessive. In the yakuza themed story segment "The Dragon of Iidabashi: Pipi's Revenge", Pipimi recruits Popuko to her crime syndicate after being impressed by Popuko's violence: she mauls a fellow prisoner in jail for using anime phone stickers despite being indifferent to the anime itself. When Popuko is later killed by rival gangsters Pipimi resurrects her and achieves her titular revenge by inciting this sort of nerd rage. Pipi approaches Popu's coffin with a briefcase and pulls out some otaku kid who, paging through a collected Pop Team Epic manga, sneers, "She said she hated subculture girls... but she sure sucked up to them." He is immediately shot by a furious Popuko, who pops out of her coffin gun blazing. Popuko is tied deeply to pop culture, but her response to it is hilariously unhinged, pathological, and incoherent.

Ready Player One's advertising seems to assume the same flat horizon of pop as pop art does, but assumes that this flatness can be invoked for a specific response. Show a person any random pop thing from a certain slice of nostalgic history, and receive a positive recognition. Receive more than a positive recognition, receive an ecstatic recognition! It's not enough just to like something, it's got to be Totally Epic, something you build your whole identity around.

But Popuko and Pipimi turn that on its head. They respond to the reproduced images of pop with the same extreme reaction, but it might be extremely positive, or, just as likely, extremely violent. Don't forget that each episode opens with a tv being smashed! And pop really is a flat horizon: Popuko might defend the honor of random anime and True Fan status with over the top violence, and she might plot the destruction of a cuckoo clock, standing with her iconic nail bat and vowing to wait and destroy the cuckoo in half an hour when it reappears, with just the same fervor.

This flatness also prompts a kind of ironic engagement with the show's own material, where things that are obviously, transparently not worthy of any sort of fervor (think: loss.jpg, the Bee Movie, All Star, Never Gonna Give You Up...) incite a passionate response just through their joking repetition. Because Pop Team Epic is produced by a number of different animators who apparently are given quite a bit of autonomy, the same skit can be repeated in multiple divergent forms across several episodes. The show repeats a skit where Popuko invents a dance called "Eisai Haramasukoi!", asks Pipimi whether it will catch on, and receives assurances that it'll be a hit several times across multiple episodes, culminating in a lavishly colored dance party sequence. This moment felt awesome to me... but it was also overtly nonsensical, juxtaposing the ramp up to the song's climax and Pipimi's passionate DJing with the overt shittiness of Popuko's singing and dancing. There's no particularly good reason to be this hype about it actually "catching on," but there's no particularly good reason to be hype about a bunch of repeated images of Campbell's Soup labels either. Nevertheless, Warhol's work endures.

Pop Team Epic, it seems, would much rather we focus on these memetic images rather than the kind of adoring subservience to corporations that we've come to expect from other producers (Star Wars, Marvel, Disney as a whole, and so on). The show begins with a tv getting smashed. It ends with Pop Team Epic's publishers Takeshobo and anime producers King Records getting destroyed by Popuko and Pipimi after they try to kill them and replace them with more marketable schoolgirl anime protagonists.

None of that suggests that Pop Team Epic as a project is less pathological than Ready Player One's marketing or, indeed, Popuko herself. Maybe all this antagonism towards the marketable is just posturing, and this shit anime has simply bewitched me with mass produced rebellion. Maybe treating media as infinitely reproduceable is always going to be a problem, and there's no way to get out of the pit of consumption without starting with sincerity and a deep, abiding respect for the sanctity of the original work.

Or maybe we just need to break more shit.

Find out in:

Let's Pop Together Part 2: Fall In Love Again Next Week

This Has Been

Let's Pop Together Part 1: Super Flat

|

You Didn't Get Rogue OneRogue One is a controversial film, but might it be the best film in the Star Wars canon? This monograph digs into the murk of bad Star Wars readings to uncover the real brilliance of this movie, and the potential of the whole franchise. |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment