2016 sucked. Let's talk about Snowpiercer, clipping., and seceding from a broken reality.

|

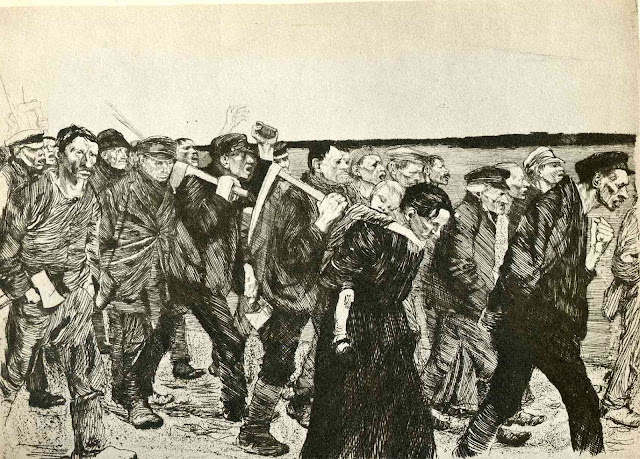

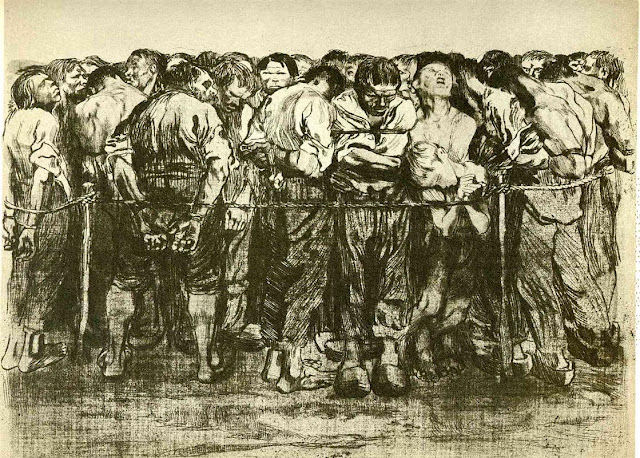

| All art in this article is by Kathe Kollwitz, queer revolutionary socialist engraver. |

Splendor and Misery, the most recent release by the avant garde hiphop group clipping., is a concept album about a revolt on a slave ship. The ship happens to be a spaceship, but that doesn't actually, it turns out, change all that much about the basic dynamics at play here. That's largely the point: Splendor and Misery is part of the Afrofuturist tradition (a tradition shared by Janelle Monae for example) and one of the recurring themes of Afrofuturist works is the way the past and the future resonate with each other, parallel each other, and inform each other. This particular work is informed by a history of enslavement, violence, attempted uprising, and reprisal.

It doesn't have a happy ending.

This is an work about a hopeless situation characterized by pain and isolation, and rather than being an abstract Golden Age Sci Fi story about the technological realities of this isolation, it is a psychological and political exploration of the larger systems that engender this pain and isolation. It is bleak precisely because it is responding to material realities, and offering as an alternative that for many listeners won't be particularly appealing. In the words of William Hutson:

Oblivion is preferable to white supremacy, patriarchy and capitalism. And the discussion was how to make it sound like piloting into a black hole feel like a powerful choice.

The whole album is based around enabling this particular affective experience, and each song, including and indeed especially "Song 5," a track in a completely different style from the rest of the album about completely different characters, plays some part in putting forth an emotional argument for an apocalyptic leap into darkness.

Snowpiercer is, properly, a post-apocalyptic film, a film after humanity, in a moment of plausible techno-utopian stupidity, pumped a bunch of chemicals into the air to counteract global warming, reducing the world to a popsicle. The only survivors left ride the train Snowpiercer around the world, surviving in various states of wealth and poverty within the closed system of the train. The train, naturally, has its first class passengers and its economy class, and the protagonists of the film are relegated, in a state of squalor, to the crowded back of the train. The narrative of the film follows a group of revolutionaries attempting to make their way from the very back of the train to the very front, facing at every turn authoritarian violence meant to preserve the holy order of this train which is the world, propelled by a holy engine and its sainted creator Wilford.

It doesn't have a happy ending.

This is a work about an untenable situation, a society of rigid Malthusian constraints and internal contradictions that is constantly on the verge of complete collapse. It is at once grotesque and horribly plausible (after all, wouldn't it be easier to just spray something into the atmosphere than try to break the stranglehold of the fossil fuel industry on the global economy?) and the key to the incisiveness of Snowpiercer's critique is its willingness to be absurd and grotesquely exaggerated.

Splendor and Misery, according to the band members, owes something to the tradition of cosmic horror that Lovecraft is most famous for. What Splendor and Misery really owes to Lovecraft in terms of horror is not merely the emptiness of space, the vast cold abyss between stars that the human mind can't wrap around effectively, but the emptiness of narrative itself. Splendor and Misery is a story in which very little happens except that a character freestyles to himself on a ship hurtling into the void and slowly but surely begins to crack.

Much of the actual action takes place in the opening song which, after the first instance of the spiritual "A Long Way Away" which will reprise throughout the album in various forms, conveys in a blistering flow the narrative of a slave ship in outer space whose automated systems fail during a slave revolt, leaving everyone dead except for one guy, the character who will be freestyling and slowly losing his mind through the rest of the album.

Oh and then I think the computer falls in love with him?

Certainly the computer decides to send out a message to pursuers to back the fuck off. Not that it matters much--it's clear that pursuit is inevitable and as a result the ship and its sole survivor avoid stars, avoid light. They are hurtling into the all black everything, and it is this dark void that pervades the album.

The album is thus a story that is grouped largely at the beginning and the end. In the middle there's a whole lot of nothing except for thoughts. It's not even necessarily structured like Pink Floyd's The Wall, an album that largely takes the form of a flashback over the main character's life as he stands on the brink of constructing his titular wall and becoming a fascist demagogue. Shit still HAPPENS in The Wall. In Splendor and Misery we get occasional glimpses of backstory but for the most part as far as I can tell it's just slices of the psyche of the protagonist and the nascent consciousness of the ship's computer.

While the band members note that part of the horror of Lovecraft comes from a white male positionality that can't cope with no longer being the center of the universe, the protagonist here, for all that he is a black man, doesn't seem to be doing that much better with the experience of being confronted with the vast void of space.

The freestyles fade in and out, are obscured by static, are clouded by the synthetic beats that they ostensibly are overlaying. Splendor and Misery is an album that is isolated from its listener, constantly on the verge of being swallowed by the void.

Snowpiercer is a hideously, inhumanly closed system. The world outside Snowpiercer is a dead world, utterly dead, utterly void. It's not the void of space though--it's clearly a once-populated void, as is made clear by the opening shot of a "SAVE THE EARTH" ornament of some sort which rattles in the cold wind as the train hurtles by.

If a void is cosmic horror in the sense of humanity being dwarfed by its vastness, the world Snowpiercer travels through is cosmic horror in the sense of a finite geography that is nevertheless deeply inhuman, underscored by the traces of the human that we can see every time we get a peak out the train's windows. The cold, unfeeling void of the universe was always out there waiting for us, but well, we managed to make it REALLY cold.

It's fitting then that much of Snowpiercer is shot like a horror movie, scored like a horror movie. There is a 15 minute sequence, for example, that could be considered a sci fi action sequence, I suppose, and could have been shot like an epic action scene. Instead, the thugs beholden to the front of the train wield axes and wear nightmarish executioner hoods, and the carnage is shot in unsettling slow motion. This isn't a triumphant battle. This is sheer butchery. And when the fighting stops briefly to celebrate the new year, this serves only to underscore, through that perverse, black humor the film runs on, the monstrosity of the violence surrounding it. Integral to this are the glimpses outside, the shots of the vast frozen wasteland that Snowpiercer rams through, making clear its name. The horrors inside the train are human ones, but the train itself and its environment are on another level entirely, something that is radically outside human control.

This daring artistry was, naturally, too much for the corporate cro-magnons of Hollywood. Harvey Weinstein, holder of the rights to the film, threatened to release it with 25 minutes hacked out and voiceovers added to turn the film into a more conventional action movie, suitable for "audiences in Iowa and Oklahoma." The parallels here to the continual assumption by Democrats that rural areas are populated purely by (white) hicks are as telling as they are infuriating. Director Bong Joon-ho, despite apparent opinions to the contrary, knew exactly what kind of film he was making: a film that didn't need to be streamlined and simplified for a parochial, blue collar audience, whose experiences the film is, fundamentally, about.

Splendor and Misery is a deeply intertextual album, and there's a LOT of allusions that I'll admit up front I don't really have a frame of reference for. Some--mentions of the interstellar communication device the "ansible" from Ursula Le Guin's Hainish novels, or the complex, queer, polyamorous cosmology of NK Jemisin's Inheritance Trilogy--I get. Others I recognize by name at least, even if I haven't read the books in question (Judith Butler's many novels, for example). There's loads that I don't recognize though whether because they're science fiction I haven't read or rappers I haven't listened to.

Oh and the title comes from a book that was never actually finished. So there's that too.

In fact there's a whole bunch of obfuscated information in Splendor and Misery. "Interlude 2" for example is a series of words making up a code which can be unlocked with a line in ANOTHER song ("The keyword is 'Kemmer,' that's what your ass need"), revealing a line that maybe refers to another story song on another album (but no one's really sure).

The result is an album that's highly metatextual in content, and an uncompromisingly dense one at that, one that is deliberately difficult to pick through, even once you get past the harsh noise of the backing tracks. The complex webs of allusion in Splendor and Misery are jumbled, distorted, andsometimes read possibly in opposition to their original intent ("The Ecumen ain't everything and these killers ain't playin'...").

Most of all, they constitute a kind of constructed mythology that can allow for totally separate stories to be invented, inserted into the narrative, and drawn into parallel with the main story without ever quite clearly being a part of them. In other narrative concept albums these stories would tend to have a framing narrative of some sort, something to clarify who is telling the story in what context--Pink's hallucinations, or the revelation of a storyteller at the end of The Black Halo. Here, songs like "True Believer" and "Story 5" are unclear in their relationship to the wider story and must be connected by thematic inference on the part of the listener.

"True Believer" in particular blends together spiritual vocals with a rhythmically recited narrative that could be the backstory of the album, but... maybe isn't. After all, in the mythology described here, the actual god Bumba interacts with Enefa, a character from NK Jemisin's Inheritance Trilogy, weirdly blurring religious traditions with modern fantasy. That's sort of the whole Afrofuturist project, of course, this collapsing of the past and future together in order to draw parallels, but it seems particularly strong here, and particularly confused, a narrative being reconstructed from fragments in the context of isolation and creeping madness.

It's hard not to read the scene in which an enraged father, faced with the state abduction of his son, throws a shoe at a high ranking train official, as a parallel to journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi's similar act in 2007 when he hurled a shoe at the head of war criminal George W. Bush.

Al-Zaidi was sentenced to three years in prison for the act of protest against what we now know was a totally specious invasion of another country based on an endless parade of lies which bourgeois media and politicians of all stripes--Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, to pick two salient examples--consumed and regurgitated eagerly. The perpetrators of those lies and the abuses that followed were, of course, never held to account and even now many of them still regularly appear in the bourgeois news as, astonishingly, reliable sources.

It's true that al-Zaidi's arm wasn't frozen off of him, but well, what's a pack of war criminals to do? You can only get away with so much. The army destroyed the shoe though. The shoe was apparently dangerous in the same way Osama Bin Laden's corpse was. It was not a shoe. It was disorder.

In that light, Minister Mason's speech is a remarkable bit of satire. Snowpiercer of course drips with perversity and black humor, and it's out in full force in this scene as Mason tries in frustration to express his disappointment that someone would dare be so utterly ungrateful. "This is not a shoe. This is disorder. This is size ten chaos. This is death."

Snowpiercer is full of dirt. It is full of matter out of place--matter that shouldn't be where it is, matter that is absent (extinct) from where it should be, shoes on heads rather than on feet. Snowpiercer is populated by dirt people, people as matter out of place, people like al-Zaidi, people like Chelsea Manning, people who are, beyond anything else, an outrage, an offense to power.

Song 5 is a spiritual about a factory worker, Grace, who fights for labor rights and is murdered for her trouble. The story follows her radicalization through the death of a "comrade," her careful documentation of abuses which might be used to take down the factory owners, and her death in a car crash, implied to be a planned murder. This song has nothing to do with the rest of the album narratively. Thematically, however, it is core to the experience of Splendor and Misery.

This is a story ripped straight from history, a long and bloody history of labor revolts and the violent resistance from above that they meet, whether through clandestine murders like this one, trumped up charges (Sacco and Vanzetti come to mind here alongside many, many laws throughout American history used to prosecute ostensibly "free" speech against war, against the excesses of capitalism, and so on), or simple outright slaughter such as the Ludlow Massacre in which children in a tent city of striking workers were literally burned alive by the National Guard.

"Once her taxi hit the curb/she'd not speak another word/O Grace what have they done?"

Song 5 therefore represents a sharp return from the science fiction of the rest of the album, which describes an experience that is distant in both past or future to the experiences of most, to the harsh realities of the present or near past. It is easy to allow science fiction to become abstract despite its resonances--look at the declaration by Disney's CEO recently that Star Wars, literally a series of films about diverse rebels fighting Space Nazis, is "not political"--so this direct parallelism is important. It provides a context that sees what the protagonist is going through as a parallel to a long historical tradition and present reality of oppression and exploitation.

And what's more, it is not a feel-good song, it is not a song in which the plucky hero wins in the end. Grace dies, horribly, brutally, and the song is characterized by grief, anger, and horror over the brutal lengths that the system will go to protect itself. These lengths parallel the self-preserving systems on the slave ship: engineered plagues designed to wipe out a revolting "cargo," new experiments in inhuman repression. This is a song not designed to leave the listener feeling that the tension of this violence is resolved. It invites the listener instead to a negative emotional experience, an unfulfilled emotional experience, an experience that, perhaps, might leave the listener to resolve these negative affects through real, material action.

And this experience leads naturally to the conclusion.

The Malthusian rationale of Snowpiercer's operation is notable. Mason talks of maintaining proper balance within the closed ecological system of the train. It makes sense. He's right--the train can only be sustained within a rigid system of control in which the environment is perfectly monitored.

The Seven, those who three years into the nightmare voyage jumped from the train in the hopes that the outside world was survivable, were also, of course, wrong. We see their frozen corpses, a "tableau" used to illustrate to children what the alternative to the class system of Snowpiercer looks like. It looks like a frozen wasteland. It looks like seven icicles in a ragged row up a hill.

For all that the Left likes to portray itself as beyond the barbarism on display in Snowpiercer, you wouldn't have to hunt hard to find many a leftist or a progressive or whatever who'd happily agree that there's just too many people on the little blue-green marble we call the Earth. A great human die-off is what we really need to sort things like Global Warming out. That's how we keep the system from collapsing.

But there it is, isn't it? There's the catch. Such a philosophy, predicated on atrocity, isn't, in fact, revolutionary at all, but merely a way of perpetuating the system. I'm not going to claim that this is how we get to Stalin, but well, I'm not NOT going to claim it. Watching the left online adopt the same tactics as Gamergate, Teabaggers, and the Alt Right is horrifying, but it is not surprising. What Wilford recognizes is that even as everyone has their place within the system, these natural orders must sometimes be disrupted--after all, it's a meritocracy, is it not?--and it's this very fluidity that allows a leftist to strike down a fascist and then slip easily into his place, to turn around and brutalize their comrades over doctrinal failings.

Once you accept the basic premise of the engine, it becomes self-perpetuating. This is a fate worse than death. The great trap sprung in Snowpiercer is the possibility of becoming the new conductor, the new manager of the engine. But you can't reform the machine--its very nature is butchery. The only thing left to do, as we see in the movie, is to put your body upon the gears and prevent the machine from working at all. From that perspective it seems obvious that the Seven made precisely the right choice. If the alternative is reproducing the maelstrom of violence and suffering, better to become an icicle.

My experience in 2016 personally and politically was one of just about every system I depended upon breaking one after another, splintering, becoming flensing shards at the moment of their collapse like a ship's mast splintering or a gun's barrel exploding. I'll leave this year having made some progress, largely thanks to a readership that seems bafflingly willing to pay me to write these depressing screeds, toward being able to survive, but at a cost to my mental, physical, and social health. I feel like I'm clawing my way towards 2017 with the last of my strength. Moreover, I think a lot of people feel the same way.

For some, this kind of context and experience demands art that soothes, uplifts, and gives hope. To me, that art tends to feel more hollow than anything else. It's not that I necessarily rule hope out entirely--there might be some way forward that doesn't involve hurtling into a black hole--but it so often feels unearned, so often feels like a way of sweeping very real experiences of despair and pain under the rug, to demand a constant affective performance of wellness and stability and optimism.

There is a value to narratives that focus instead on failure and disaster. Kathe Kollwitz produced a series of prints at the turn of the century depicting medieval peasant revolts, and the conclusion of this pictorial narrative is violent repression. Kollwitz is a revolutionary socialist but she does not invent reasons to feel triumphant when there are none, just as Howard Zinn, in his People's History of the United States, from which I draw much of my knowledge of the history of class struggle in the country, does not invent triumphs for the oppressed. Zinn unflinchingly tells of both the abuses of power, and the failures of workers to unite along racial, gender, and doctrinal lines, the violence both imposed from without and from within.

If we are going to tell stories about resistance, surely it behooves us to tell some stories that actually have fucking anything whatsoever to do with that historical reality.

This is the narrative offered by Snowpiercer and by Splendor and Misery.

Not that these narratives are fundamentally without hope. It is possible that the protagonist of Splendor and Misery might be able to "survive the gravitational shift," survive being ripped apart on an atomic level to find a better universe. It is possible that Yona might survive Snowpiercer's apocalyptic crash at the end: the final shot of a polar bear proves that, yes, the outside world IS survivable, as the Seven believed.

The point, though, is not to guarantee success or even to suggest that success is likely. It is to present staggering odds after portraying a fundamentally unacceptable status quo. To put this in Gnostic terms, the point is not to focus on the hope of a transcendent successful escape from a fundamentally broken reality, but to see that broken reality clearly for what it is and to made a determination that this broken reality is not acceptable, even if it encompasses the whole of the universe, even if it is baked into matter itself on a subatomic level. The point is to be furious, but in that fury to find a clarity of vision that comforting delusions (The Electoral College will save us! Russia hacked voting machines! The Democrats can reason with fascists and moderate their opinions! We can find a reasonable compromise between electrocuting NO autistic and queer kids and electrocuting ALL autistic and queer kids and this middle ground is actually the best plan! Leftists will support each other with mutual aid and definitely won't continuously enable charming abusers or viciously scapegoat people for writing the wrong kind of fucking fanfiction!) obscure.

What does that look like in terms of a plan of action moving forward? Fuck if I know. If you have a black hole handy for me to hurl myself into, do let me know. I don't have any bright or uplifting message to offer, despite this being the season of comfort and joy. I'm with Tom Waits and Peter Murphy here: "when it's your career to be down in the dumps/tidings of comfort and joy really suck." Though at least I can have somewhat of a sense of humor about how grim I'm feeling these days.

One thing I'm not going to do though is pretend that everything is going to be ok, or that 2016 wasn't an abject clusterfuck of a year. And in that sense, I think it's exactly the right time to consider works like Splendor and Misery, and Snowpiercer, and the complex political and affective experiences they offer, and use them as a jumping-off point, even if that might mean jumping off into a cold and uncharted territory.

See you in the new year, or on the other side of the black hole.

No comments:

Post a Comment