"Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing..."

"In place of you, who could accomplish anything but won't, I am suffering in your stead!"

Since we're on an optimistic streak of late, I want to talk a little bit about Madoka Magica. This might seem, at first glance, like an odd choice. The show, for folks who are not familiar (and if you're not familiar I don't recommend reading much further, as it's impossible to discuss the show's thesis without discussing a whole raft of rather serious spoilers) is a deconstruction of the Magical Girl genre popular in Anime. It's kind of like Cardcaptor Sakura or Sailor Moon, but the idea of teenage girls going out to battle cosmic evil is treated much more psychologically seriously, and a whole lot of suffering ensues. It's a beautiful show, but it will tear your heart right out. So, yeah, seems like kind of an odd choice for Optimism Month or whatever we've got going on here on StIT.

Except, I don't think pervading despair is, despite all indications to the contrary, really the most important aspect of the show. In fact, I would argue that the show is a deliberate and explicit argument against despair--and, more importantly, the acceptance of wretchedness as inevitable or even acceptable for the sake of a greater cause.

To dig into why, though, I want to talk a little bit about a story by famed science fiction and fantasy author Ursula Le Guin. The story in question is entitled "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas," and it can be read, in full, here. It's not long, so I'm going to kind of assume that you read it before we begin.

Ok?

So, to sum up what you definitely just read as I instructed rather than blowing off my request completely while rolling your eyes, the main premise of the story (if you can even call it that--it's almost more of a thought experiment) is that there's this city--the most beautiful city ever, where everything is basically fantastic.

But Le Guin suggests that we might not buy such a town. That we have to have something to make it more believable.

So she introduces a child that suffers a wretched and debased existence, kept within the perfect town--someone damned so that the joys of the rest of the town can be given significance and meaning.

And then she suggests something interesting:

The townsfolk are introduced to this child's existence at a certain age, and most accept it as a simple fact of the town's existence and use it to provide a context for their joy. But not everyone is willing to accept the joy of the town, once they understand the child's existence.

These are the titular Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.

And they cannot accept the price of their joy.

A part of me is tempted to just sort of lazily close the article here and let the text and pictures talk for me, but I actually wrote this bit last and the next bit first so I guess I'm kind of stuck now, huh? Whoops.

Anyway, I think it's worth digging into the comparison I'm making there a little more deeply in order to pick apart the ideas expressed within the show. It's helpful, I think, to compare it to Le Guin's tale, because she is quite explicit in the moral of her story, or at least the broader moral question she hopes to raise, whereas the show can be, at times, maybe a little more difficult to untangle (but only a little!).

Let's start by talking about Omelas and its relationship to the broader setting of Madoka Magica. The setting in these stories is important, and it's worth exploring how MM's setting is introduced, especially compared to other anime.

Remember the whole sequence in the first episode where the teacher rants about the proper way to cook eggs?

|

| This one. |

| In contrast: Fullmetal Alchemist, which uses superdeformation to indicate tonal shifts quite effectively. |

This is simply the reality in which Madoka lives.

And it is completely frivolous.

The fact that the show remains in a realistic mode of staging emphasizes the fact that this is just what daily life is like for Madoka and her peers. There's no stylistic switch to indicate a change from the serious, plot-relevant parts of the show, and the frivolous, comic relief parts.

I think it works more successfully than, say, Code Geass, which never quite managed to juggle its tonal shifts effectively (for me, anyway--obviously, it worked just fine for many, many other viewers). But it's worth making the comparison to that show because they both have a similar aim: the simple, largely carefree lives of the elite are being set in opposition to the suffering of a few. You can sense it as soon as Homura walks into the room: there's just a fundamental difference from the awestruck students and the cold, broken warrior. She's conscious--hyperconscious--of how thin the eggshell of the world really is, and how tenuous the cuteness of the first three episodes really is. Interestingly, though, this only becomes clear on a second viewing. On a first viewing, the endless prettiness is just glorious eyecandy that we drink in.

On a second viewing, though...

|

| Me too, Homura. Me too. |

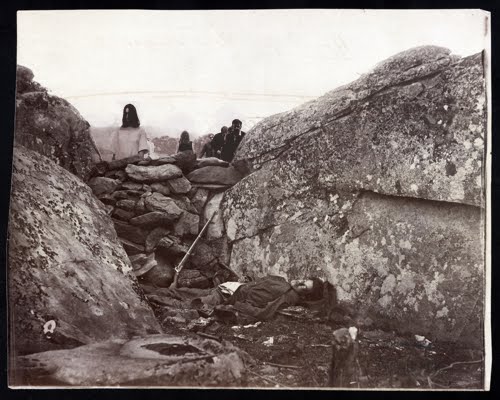

And part of the reason for that is that I had seen the graves upon which that cuteness was built. It is built on the suffering of teenage girls. Which is, especially when you put it so bluntly, pretty fucked up. All those beautiful, airy buildings can only exist in a world where teenage girls fight beings that are literal suffering and anguish made manifest, only to eventually die or, worse, transform into those sorts of beings of literal suffering themselves. The people that live in Madoka's world are the same as the people of Omelas--living in bliss through the suffering of a few.

Perhaps this judgment is not completely fair. The thing about Madoka is that the character's--the side characters, I mean--aren't bad people. And really, it's not quite fair to compare them to the people of Omelas. After all, they have no idea that their world is so beautiful, so rich in multiple senses of the word, because of the suffering of Kyubee's targets.

But still, it's hard to shake that feeling that there's something corrupt about the show's joy. In many ways, the show takes great pains to lead us to that conclusion--Madoka's repeated cry that it's "just too cruel" comes to mind. And while Kyubee's race seems to have good intentions, their minds are ultimately quite alien, and Kyubee's own reaction to Madoka's suffering is not the reaction of the people of Omelas--it is not a reaction that acknowledges the suffering and responds--it is a dispassionate response of a being that sees humans as tools or livestock--a convenient power source.

So, what is all this trying to say?

Well, one of the things a lot of readers seem to overlook with LeGuin's text is her critique of imagination. It's very easy to get caught up by the philosophical question of whether or not we should accept a paradise built on foundations of suffering while missing her underlying question. Here's probably the most concise expression of the question within the text:

"The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain. If you can’t lick ‘em, join ‘em. If it hurts, repeat it. But to praise despair is to condemn delight, to embrace violence is to lose hold of everything else. We have almost lost hold; we can no longer describe a happy man, nor make any celebration of joy."And, of course, Le Guin is a great writer, so she goes further than simply posing the problem, she forces us through it by describing a paradise, and then demanding that we confront our reaction to it. She says, her, let me add this element of suffering. Is this more plausible to you? And from there, let us ask: why do we find it so difficult to imagine a paradise without a dark halo? Why do we find it so hard to believe in goodness and peace? Why do we accept the "treason of the artist?"

Of course, some of this might be because it'd be hard to write a story without some conflict, but there's conflict and then there's conflict, you know? There's conflict in a Hayao Miyazaki film even if there isn't always a lot of suffering, per se... it's part of why his villains are often so much less villainous than you would perhaps expect if you've grown up on Disney films.

But LeGuin seems to be asking us to dig a bit deeper into our own psyches and question why we glorify evil, essentially. This is a particularly relevant question when discussing a deconstruction like Madoka, or Neon Genesis Evangelion, or Revolutionary Girl Utena, or the newest Batman and Superman films. Why are we compelled to take relatively bright worlds and dwell in their penumbra?

Why does LeGuin feel compelled to introduce her suffering child into the bright city of Omelas?

Well, what both Madoka and LeGuin are getting at, I think, is that we have to be willing to directly confront our tendency to find darkness in light, both as philosophers and as artists. In fact, there is an inherent challenge within these stories to find more optimal solutions rather than simply accepting a tainted reality.

After all, isn't that just what Madoka does?

Madoka is one of those who walk away from Omelas. And her choice has real impact because we have grown to deeply sympathize with the tortured child in this scenario: Homura. (And to a lesser extent Sayaka and Whatsherface, of course.) In fact, the emotional arcs of the story are meant to deliberately bring us to an understanding of why Madoka must inevitably make the kind of wish that she does ultimately make.

This is, incidentally, one of the many brilliant narrative tricks of the show. The relationship--the love--between Madoka and Homura is not incidental to the show's themes. In fact, it is Homura's agony--her deliberate taking on of pain in order to support Madoka's paradise--that allows us to see the horrible human consequence of the Faustian bargains made in the show.

In fact, Homura's first speech to Madoka in the conclusive timeline of the show is a declaration that she must never swerve from who she is--i.e. she must never attempt to crack the eggshell of the world and discover the rotted core--if she wants to continue living in bliss. Homura knows, you can tell that she knows because of her facial expression, that in doing this she is forfeiting her own happiness. She is willingly choosing the path of the martyr for Madoka's sake.

This introduces a crucial difference between this series and Le Guin's text. For Le Guin, the Child is one character, and the Omelans... Omelasians... Omelamas... ah, let's just call them the Townsfolk, is another "character" (the third being the ones who walk away, of course). In Madoka Magica, in contrast, the Townsfolk and the Child are one--the Magical Girls are both the sufferer, and the people who accept that suffering on some level (either by enjoying their lives understanding their Faustian suffering, or by embracing and ultimately becoming an embodiment of suffering and hopelessness--either way, there is acceptance of suffering as inevitable and ultimately, in some way, permissible).

Homura is the ultimate example of this, of course, although all the other magical girls express it to a greater or lesser extent. In fact, one might argue that Homura is the only truly significant example, as, in some ways, she has the most free will of any character. She's similar to a character like Paul Atreides from Dune: she has an imperfect kind of prescience, in that she has seen multiple possible futures and is capable of acting with full knowledge of the way other characters behaved in other timelines. It is, as I say, imperfect, but ultimately other characters are put in a reactive position to Homura's iterative actions as she continually attempts to a future in which Madoka is saved.

It is significant, then, that she never sees a possible victory beyond Madoka's personal salvation. This is why Homura, for all her power and autonomy within the various timelines, is ultimately still trapped. She willingly traps herself by accepting that her own suffering and the suffering of the other magical girls is inevitable. She is one of the Townsfolk--or one of the traitor artists--accepting that a paradise can only exist if someone, somewhere pays a hideous price.

Madoka, then, is the perfect counterpoint to Homura's demigodly despair. She is the only agonist capable of canceling the despair that pervades the universe. It is interesting to me that not only does Madoka retain the powers of her previous iterations, she seems to retain some glimpses or fragments of memory, as seen in the first episode. While Homura can map out possible futures, she can still be caught off guard--she is not omniscient--and Madoka, in particular, has the power to surprise her, perhaps in part because of her ability to sort through Homura's iterative futures and find a way out that Homura herself cannot see.

Madoka sees the Suffering Child and decides that such suffering, even for her own happiness, even for her own humanity and continued existence in this world, is unbearable.

Madoka perceives the rules of Kyubee's game, and short circuits them.

She does more than walk away from Omelas--she rips out the foundations of the whole fucking city.

To me, it's pretty clear that the show is more than a revisionist reimagining of the Magical Girl genre. The show tears down the trappings of the Magical Girl only to tear down the trappings of the revisionist narrative as well. Remember that Le Guin is interested in pointing out the treason of artists--the willingness of creators to accept evil as something that must exist for there to be beauty. This show asserts, in its own way, the same basic idea. The cynicism of Homura is shown to be a weak and mortal thing in the face of the boundless love of a goddess willing to see a path out of suffering. So, too, is the cynicism of the deconstruction shown to be ultimately insignificant in the face of profound optimism and a belief in beauty not tainted by darkness or diabolical compromises.

Madoka's ascent is accompanied by one of the most stunning lines in the entire show:

"If someone says it's wrong to have hope, then I'll tell them they're wrong, every single time."

The brilliance of this line comes from the fact that it is a logical "If-Then" statement. If x, then y. And for Madoka, this statement is more than just a declaration or boast. It is literally a new law, written into the very fabric of the universe itself. She has reordered reality to make this refutation an inevitability.

It is an inevitability that supplants the inevitability of wretchedness.

And, to some extent, I can't help but wonder if as an artist part of my own role in the world should be to take on Madoka's declaration and hold it close to my work and to my heart. There is certainly a role for deconstruction--there is a purpose to the exposure of the Suffering Child, the exposure of wretchedness, the exposure of how people in our society are shut out and tormented and made to believe that brutality is the only law in the universe. But is it really enough to hold a mirror to society? At what point does the exposure of the wretched become to us, as it becomes to Homura, an inevitable damnation to be accepted, a burden that we take upon ourselves?

In the end, whether you struggle forever accepting your own ruin, or transform into a Witch and accept the ruin of those around you, have you made a truly significant choice?

Le Guin's story and this short, concise cartoon demand, ultimately, the same reflection from us as critics and artists.

They demand that we ask ourselves whether or not we are among the ones who walk away from Omelas.

|

You've Got To Throw Your Zombies On The Gears!Solarpunk's utopian vision is broken. It's going to take some weird lateral moves to fix it, and one strange Steampunk strategy might offer a solution. |

|

|

Homestuck, Destiny, and why Social Constructs are BullshitSam Keeper has something to say about the way Homestuck deconstructs social constructs of romance, heterosexuality, and hierarchy, but to explain it she'll have to confront a series of diabolical opponents: alternate timeline versions of herself. |

|

Just saw some episodes...

ReplyDeleteThe town style and design is good,

but all the girls are one-dimensional, and the story is uninteresting.

If anything, Homura, the dark-haired girl, is not one-dimensional, literally. She traversed time and space for someone and is more than Hardboiled Serious Mcbadass.

Delete"some episodes..."

DeleteThere's your problem. You have to watch the whole show before you can judge it. It's only 13 episodes, get going!

Yeah, if you're going to watch it, you have to watch the whole thing. It starts out like pretty much any Magical Girl show, doing pretty much all the usual tropes and stuff. But then it changes. That's what the "deconstruction of the genre" thing is about. After, like, the 5th episode at most, you realize that things aren't one-dimensional, you've just been forced to view things from an absurdly skewed perspective.

DeleteI was psyched to see you'd written an article about Omelas, which I read when I was little and have never forgotten. But then you said don't read it if you haven't seen MM, which I haven't. But then I decided to forge on anyway, spoilers be damned, since I already had a vague secondhand idea what was up with MM and I didn't think I was likely to watch it in any case.

ReplyDeleteI feel like that was both the wrong and right decision. Wrong, because you've made MM sound pretty interesting and now I do want to see it. Right, because if it holds up to repeated viewing, does it matter if I know some of the things that happen? Spoilers shmohelers.

One thing's for sure, I don't regret reading this article. I remembered vividly the moral dilemma that the child posed to the townsfolk when I, the reader, accepted the premise. But all this time I never realized that my acceptance of the premise was such a central question in the text. Why is it so hard to imagine a place like Omelas with no wretched child? I've got a lot to think about.

I am pleased that someone take the time and wrote about this masterpiece (Mahou Shoujo Madoka Magica) ,with such detail and understanding because it certainly deserves.

ReplyDeleteYour essay reminded me of one of Zizek's, wherein he argued (for similar reasons) that Christianity is inherently communistic (... which is standard Zizek fare, and makes sense when he explains it). Specifically, he thinks that "turning the other cheek" is an inherently transgressive act because it breaks the economic model of morality (as epitomized by karma, wherein good deeds and bad deeds are calculated on some kind of cosmic spreadsheet at the end of each life, and the remaining debt is turned into bad luck). Somehow, he managed to completely miss that idea (stopping the wheel of karma) in Buddhism.

ReplyDeleteOf course, the problem with systematically transgressive acts (and, for that matter, with deconstructions) is that some people won't comprehend them (and, in fact, without analysis of the type you are doing, they are not even visible). There's always somebody who claims to be Buddhist and then goes on acting like karma is inescapable, just like there's always somebody who likes Evangelion because of the giant robot battles. Madoka can get away with a subtly transgressive act because she is a god, and can encode her subversive thoughts into the underlying nature of a new universe (which, in a sense, makes Madoka Magica's penultimate scene more meaningful and interesting than the similar sequence in Serial Experiments Lain); for the rest of us, even exposure will not work, and only living and breathing a world with such assumptions (say, reading a whole series of books set in the kind of world Madoka creates -- just as Heinlein readership essentially created a population of naive nationalist libertarians without ever being totally explicit about it) will cement the ideas.

After reading "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas" I was angry as hell. First of all because I *can* imagine perfect civilizations without the need for a child being tortured and second of all since the only options the story presented were accepting or moving away. Where's the third option: rescuing the freakin' child, consequences be damned?

ReplyDeleteBut then your article made it all okay. You showed the third option. Madoka's option. Screw the rules I'll fix things.

I'm not an artist myself, but I think artists can show not just how fucked up the world is, but also that there's a way out.

"Whatsherface"

And I must admit I laughed harder at this than I probably should.

"But one story has more lesbian schoolgirls and therefore is infinitely superior."

ReplyDeleteBless you.

Urobuchi Gen (the writer behind Madoka for who doesn't know) loves this theme allright. In Fate/Zero, there are lengthy sections dedicated to the problem of the suffering of the minority for the good of a majority (and an entire section dedicated to straight out logically demonstrate how fucked up that logic is). That show has some excellent moments, though the ending is kind of bad (since it needs to fulfill its role as a prequel to Fate Stay/Night, which is not nearly as good). I also hear that Psycho Pass has a similar theme. Suisei no Gargantia is not entirely Gen's work, and even though it hosts the seeds of the problem, it never really delves deep in the question.

Besides that, I feel that this kind of ties in with another problem that I really hold dear: the fact that our society assumes man to be necessarily 'egoistic', and all altruism to be either helplessness, silliness, or belonging to the realm of utopia and dream. I think that's at least part of why we think a 'happy' society to be impossible, and why we're fascinated by deconstructions and darker and edgier rewritings of bright worlds: because we don't want to admit that there's even just a glimpse of truth in those worlds which suggest that happiness could be ours were we to care a bit more about each other and the well being of everyone else. In a sense, maybe be enjoy deface what causes us shame.